by Peggy Stevens

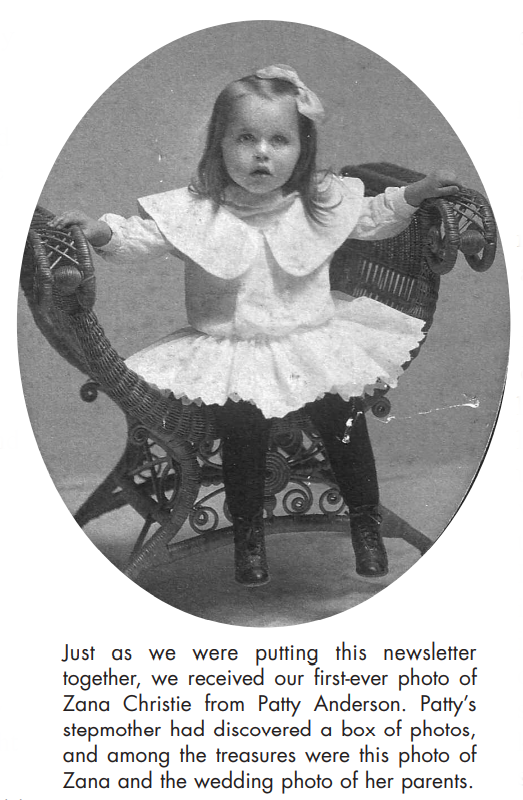

(This story was graciously provided by the author, Peggy Stevens of Charleston, VT. It appeared originally in the Glover Vermont Historical Society website. We hope you enjoy it! – Vermonter.com)

What's it Like Living in a Vermont Haunted House?

Part I: The Mystery

Late in 1974, I met a ghost. In retrospect, this visitation was a gift, though at the time I could not appreciate it as such. Nor did it occur to me to try to discover whose ghost it was; that implies a degree of fearless objectivity I did not possess. As is so often the case, it is not what we want but what we don’t want that motivates us, and all I knew for sure at that time in my life was that I didn’t want to be haunted anymore. So I moved on, though moving meant leaving more than my ghost behind. In my effort to escape the shame that came with running from a ghost, I sealed off that memory, choosing not to share my encounter with even my closest friends over a span of many years.

It was much later as a middle-school English teacher that I dared to face up to what I had spent years evading. Encouraged by the most supportive of listeners, my classroom full of enthusiastic adolescents, I finally told my story out loud. That was fifteen years ago, and by then nearly twenty-five years had passed since my brush with the supernatural. That’s how long it took for me to put into words the harrowing experience that had lingered with me for decades. And if not for promising my unduly exuberant students in my first year of teaching, “I’ll tell you a ghost story at Halloween, if you’re good!” I may never have done so. I realized as I prepared my narration that I was still shadowed by my fear of that ghost as well as the fear of what others might think of me if I dared to speak of it. That trick of classroom management was a Halloween treat for my students that swiftly became a favored annual tradition. The act of turning my private nightmare into a lesson in the oral tradition of storytelling somehow gave me a distance I could handle, a way to explore previously forbidden internal territory. To my surprise, in each subsequent year, my new students would clamor to hear my story on the first day of school.

Having heard rumors from previous listeners of the tale of terror to come in Mrs. Stevens’ class. I’d respond, “Be patient; be good!” with a bewildered smile. How strange that my most miserable past would become their most pleasurable present? And how marvelously easy it was for my children to embrace as true what most grownups might so easily dismiss as fabrication, or worse, delusion.

My narration began innocently enough with my arrival in Vermont so many years before.

It was a glorious August weekend when I first came to Glover, Vermont, one month before my twentieth birthday in 1973. The occasion was the marriage of a college friend on a remote pond, miles from nowhere on dusty back roads. The sky could not have been bluer, mounds of cumulus clouds were no more brilliantly white than they were that day. The green fields bent to the breeze; wildflowers crowded the roadsides. Here was the most peaceful and beautiful haven on earth. My husband and I, too, were newly wed, and we were awestruck.

Vermont, we realized, was the place we wanted to make our home, away from the noise and confusion of the “flatlands” (as the locals called the states south of Brattleboro) where we’d grown up. As undergraduate students of anthropology, Camden journalist Robert Houriet’s book, Getting Back Together, inspired us. Therein he chronicled the counter-cultural movement of the ’60s, including his own experience of living communally in Vermont. The seed planted then was nurtured by our visit to Glover. On our way back to where we lived at the time, upriver from New York City, we became determined to pull up stakes, find a house in the Vermont countryside and get back to the land.

As only was possible in the economy of that day, we scrimped and saved enough to provide for our first few months’ living expenses, and by Halloween we found ourselves driving back up to the Northeast Kingdom — the northern and easternmost corner of the most rural state in New England— popularized decades earlier by then Senator George Aiken. It’s a good thing we couldn’t find that house in the country we imagined, for if we had we’d never have lasted through the first winter. A warm and cozy apartment, at first a huge disappointment due to its situation in the little city of Newport, five miles south of the Canadian border, became our haven from the brutal wind and blowing snow that soon came rushing up the hill from Lake Memphremagog.

True, it uncomfortably resembled the cityscape we’d left behind, shops and houses crowding in on all sides, but the $150 a month rent, which included utilities and cable TV, made its location easier to live with. In little time, we made new friends at the local food coop and in the cave-like underground bar, Gantre’s, where natives and newcomers hung out in the frigid evenings of our first winter. Music and laughter bridged any differences in origin and culture, and many relationships formed back then remain true today. We spent considerable time there in the company of the seasonally under and unemployed, as job hunting in the onset of winter proved daunting.

The Newport area was and remains dubiously distinguished by its claim to having among the highest unemployment rates in the state. Eventually, our savings ran out, and though my husband finally found work in the local lumber factory I remained unemployed, a state not unusual for wives of the time whose profession was “homemaker.”

I was happy in that role at first, honing my cooking and baking skills. I sewed curtains and clothes and kept a tidy house. With time to spare, I played cribbage and chess with other jobless friends, read stacks of books, too, but as the gray winter months wore on the slicing wind and numbing cold trapped me indoors. I was encouraged to try winter sports like cross-country skiing, but the thrill eluded me. Though I did not regret our move to Vermont, frustration with my housebound situation crept in with the frost under the door. Learning that “cabin fever,” with accompanying high rates of depression, alcoholism, and suicide, was a common malaise in the far northern winter did nothing to ease my mood. In spite of these challenges, the long winter months were finally behind us and soon forgotten with the coming of spring.

We made the move out of Newport in April to a village better suited to our vision of country living.

By now, my husband had a good job with the state, and our six-month lease on a little ski cottage provided a setting in which I could practice new crafts, including gardening and quilting. My only companion was our dear kitty, Buckwheat, and my only company the occasional friend or neighbor who’d drop in to visit. Few of our friends lived anywhere nearby. I had no car and so was isolated, which I didn’t mind at all. Although I was alone, I was never lonely, always busy. Spring seedlings turned to summer crops then fall harvest, marking the celebration of the first anniversary of our move to Vermont.

As the coming winter threatened to close in, gray, lowering skies became the backdrop to stark tree limbs, whose stripped leaves cycloned on the frosty autumn wind. Our seasonal lease threatened to expire before a new opportunity presented itself, and my scouring of the daily For Rent ads took on a desperate feel. Finding a place that accepted pets was a challenge, but not a choice. Buckwheat and I were by now closely bonded through all our days together. She was my constant companion. I had spent more time with her than with my husband, in reality, and we could not be separated. Finally, in a turn of fate that seems portentous today, I discovered an ad in the Wanted section of the local paper: “Live-in couple to care for our home. November 1st to May 1st”. We rang up immediately. It turned out the house concerned was in Glover, and the homeowners in as dire need as we were of finding the right match. An invitation to dinner the next night was swiftly arranged.

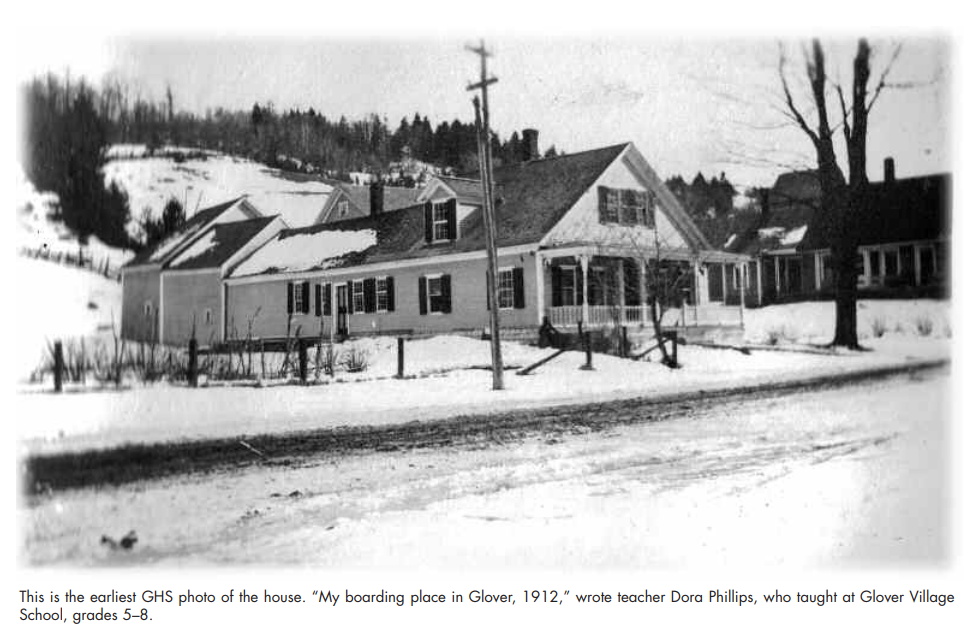

It was nearly dark as we drove into Glover Village, where we’d fallen in love with Vermont just a little over a year before and to which we had regularly returned for the monthly co-op dances at the Glover Town Hall. People came from miles around to enjoy these gatherings. Local bands played into the early morning, dancers reluctant to see the night end. It felt like coming home. “Last house on the left before the road starts uphill,” I read from directions I’d jotted down less than twenty-four hours before. The front porch and dormers facing the road were features I made out of the gloom; a small barn loomed beyond an attached garage. Through sparkling windows, lights shone within, the warmth and glow so inviting. In a state of anxious anticipation, we made our way up the steps from the driveway to the house. The opening of the door preceded our knock, as Jean and Arthur Scofield swept us into their den warmed by a crackling parlor stove. Coats were gathered and hung and introductions made. I took in my surroundings. The woodwork glowed, the antiques suited perfectly the old farmhouse-turned village home. How lovely, and no wonder Jean was looking for an experienced housekeeper. She was reassured to be leaving her home in the hands of one who could capably maintain her possessions in exchange for monthly rent. The fact that I did not work outside the home was, from Jean’s perspective, an enhancement, just as I had begun again to view it as a hindrance. The Scofields were looking for someone responsible to make sure the furnace performed, the pipes didn’t freeze—pressing homeowner concerns in cold climates. Here was our opportunity! The Scofields and we were made for each other. Over dinner, we got to know Arthur, a retired Connecticut carpenter who had moved to Glover with Jean in 1969 along with their then high school-aged daughters. He had remodeled this old house, then in a worn and musty state, to one of near historical perfection. He cared, as Jean did, that winter’s ravages not mar his careful restoration of their home. It soon became obvious that we were the winning candidates in an uncontested race.

Why on earth had no one else taken advantage of this fabulous offer?

I couldn’t imagine. By dessert we were sealing the deal, getting down to details. A quick tour around their first floor living space revealed that the central dining room had eight doorways leading off to the den, kitchen, bath, second floor, and cellar stairs, and to the front hall, which was flanked by the bedroom on the right and the front parlor on the left. Arthur assured us that we would be comfortable living on one floor, as they did, and that keeping the door to the upstairs shut tight would keep the heating bills down during the current oil crisis that saw those costs go through the roof. Arthur requested that we keep the parlor off limits, door shut as well for the same reason. We took it all in and vowed to follow their explicit directions in the interest of frugality.

As we prepared to leave, I remember Jean saying, “Old houses can be quirky.” Any odd sounds we might hear, she reassured us, were “just the sounds of the house settling, or snow falling off the roof.”

Words spoken so comfortingly, without a shadow of deception which most assuredly was there, and which Arthur in his silent assent abetted. Keys in hand we parted, prepared to move in on the day after next, October 30th, as Arthur and Jean departed for Florida. All the way home that night, we marveled at our fabulous good fortune. The next day found us packing, and early the following morning we packed our few furnishings and assorted possessions, including Buckwheat, into our Dodge pickup. The sun shone brightly as we pulled in to Glover, past the general store, town hall, and church on the right, turning left into the driveway. We quickly unloaded, the only hitch occurring as Buckwheat madly resisted our attempt to carry her in to her new home. She writhed in my arms, and as I set her down in the den, her back arched and tail bristled as bushy as a caricature Halloween cat. It would have been funny if she weren’t so upset. With a furious growl she made for the bedroom, vanishing under the bed skirts, refusing for hours to come out in spite of my coaxing. “She’ll get used to it,” I told myself, “eventually.” And as we ate our first supper at Jean’s shiny dining table, Buckwheat did slink out, wrapping herself around my ankles and staying close all evening. By 7:30 the next morning, we’d said goodbye, and I watched the truck back out of the driveway, my husband off to his job in Newport twenty-five miles away. I was left alone with recalcitrant Buckwheat still lingering under the bed.

As I prepared to meet the day, it struck me that housekeeping in this efficiently laid out living space would be a snap. I fetched my supplies from the laundry room beyond the den, noting a back staircase leading up to the closed off second floor I’d yet to see. I returned to the den with vacuum cleaner and dust cloths and within an hour or so had completed my first round of maintenance. I would have plenty of time to spare for domestic activities that had begun to feel limiting in previous surroundings. These now seemed so inviting to a young wife in such a fine home. I looked about, satisfied, for what to do next. Pulling out Jean’s red–checkered Betty Crocker Cookbook, I scanned for new recipes. It soon dawned on me, however, that the hush of the morning was dimly oppressive. This was a deeply quiet and dark house, at least this time of year. A bank rose up on the southern perimeter, a copse of trees crowded in, shading the tall windows that should have been well situated to receive sunlight. Snapping on lamps and overhead lights did not dispel the gloom.

But this was Halloween! A quick walk up to Currier’s Market, I decided, for groceries and candy for the trick-or-treaters, was just what I needed to brighten my day.

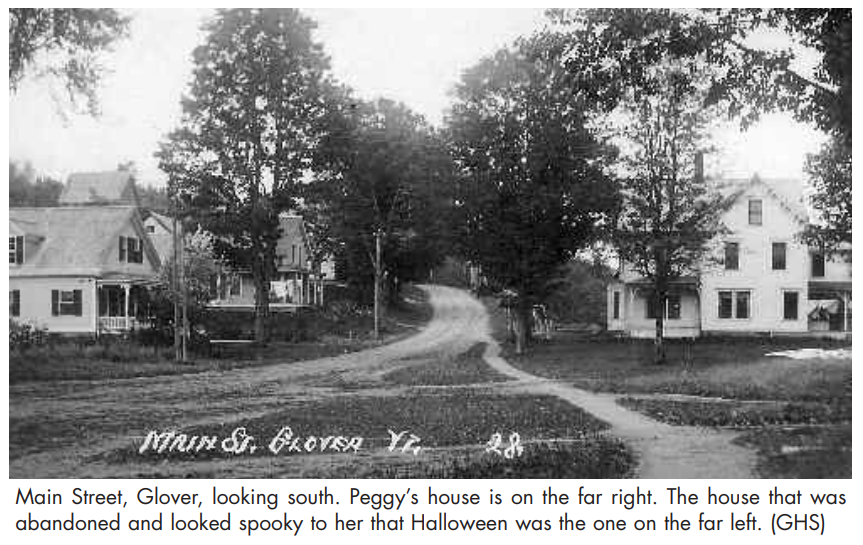

I threw on my coat and headed out to the main street through town, running north to south. Wooded, steeply slanting hillsides encroached, forcing houses in the village to crowd together by the roadside or find footholds as they perched above it. Gray winter light filtered through a mackerel sky, warning of flurries to come as they do almost every Halloween in this corner of Vermont. Entering Currier’s general store was a bright contrast to the day outside, as welcoming faces peered from behind the counters and idly curious customers smiled in welcome. Though I’d run into some grumpy folks who wished the flatlanders like me would go back where they came from, most strangers I’d met up here were startlingly friendly. The storekeepers seemed to know who I was before I introduced myself and to approve of the Scofield’s decision to have us in. I left cheerful, my good spirits restored.

The only other people I could see were to be found at the Busy Bee, a tiny diner right across from the market, which appeared to welcome locals early for coffee and breakfast and to close right after lunch. I decided I’d venture there soon, being too laden with shopping bags to stop then. The way home allowed me to appreciate the array of historical buildings clustered along the road, mostly white clapboard, occasionally brick. The town hall, a stately church, and an imposing building proclaiming itself a nursing home, though surely originally an inn, inhabited their spaces grandly. The renegade yellow paint of the Scofield house shone, welcoming, as I turned in to the driveway. Smoke from the stove in the den curled low over the roof, the woody smell of winter wafting over me as I entered the den. Busy in the kitchen putting groceries away, I heard a knock at the door that opened onto the driveway, which was the main entrance to the Scofield home.

The front door, the formal entrance to this house, faced the road, opened on to the porch, and clearly was never used. An imposing series of locks and bolts barred the way to strangers who didn’t know better. The knock came again, sharply, as I stepped to answer it, but I opened the door to no one and nothing. Leaning out, I looked to the road and back to the garage, calling, “Hello?” into the nearly November wind. I backed into the den then heard another knock, but this time from behind me.

Turning to the door that led to the laundry room—situated in the back wing that had been a mud room and woodshed originally, with the back stairs and summer kitchen beyond—I reached to open it when I caught sight of Buckwheat. In that instant I heard again that fearsome growl, so unlike the robust purr I knew so well. Back arched, golden eyes burning lasers, she glared at the wall between den and laundry. Again, the knocking, insistent and loud, caused Buckwheat to nearly levitate in response. My own nape hairs rose in fright, as much in fear of this unfamiliar hellcat as of the belligerent rapping. I tore open that door to the back wing, in the same moment wondering if I should be locking it.

Who was in my house and how did they get there?

But again, there was no one. “Who is it? Who could it be?” I demanded, comforted by Buckwheat’s attentive gaze as much as by the sound of my own voice. Then I realized, “It must be a branch knocking against the house in the wind!” I snatched my coat off the stand by the door and barged out, striding up the driveway. I turned to look up at the roofline, continuing to scan along the dormers as I strode out to the front of the house and along the road. No trees stood within reach of the house as far as I could see, no branches near enough to touch. No banging shutters or dangling gutters. Nothing untoward.

Retracing my steps, I reentered the house on guard, ready to explore the wing beyond the laundry room when the knocking came again, this time from the central dining room. A quick glance showed no presence inside, and back I ran, out to the driveway, on to the road. I crossed again in front of the house, turning to look around before figuring out how to make my way through the side yard, overgrown as it was. Beyond, across the highway, where a dirt road turned off to the west, loomed that big, white house I had barely glanced at previously.

Now I saw it for what it was, abandoned, un-curtained windows blank. The classic Halloween haunted house.

I shivered. Looking back to the Scofield place, a shaft of light played across the front windows of our new home, and what had seemed moments before a cold and unfriendly facade warmed as brilliant sunshine broke through. The contrast to its unkempt neighbor across the way was reassuring. More calmly now, I surveyed once more for the flapping shutter, the errant branch. The last of the autumn leaves clung stubbornly to distant branches, rattling in the wind. Those that had fallen skittered almost playfully across the scrim of frosted grass at my feet. Heartened, I continued my investigation with a sense of curiosity; the forbidding tangle of weeds now appeared faintly as a path worn to a clearing beyond the house, the traces of the old barnyard.

There was the broken-down fence, the suggestion of a paddock where the Scofield girls or others before them pastured their horses, which they stabled in the attached barn extending beyond the laundry room wing. That must have been a good feature, to be able to walk to the barn from the house without going outside in wintertime. For an instant, I had a vision of what this little farmstead must have looked like long ago, carved out of the forested hillside when the village was young. Having reached the fence, I turned and looked up again for offending loose house parts but found none.

Surprisingly, the back wall of this house was unpainted, or rather the paint was worn nearly away, a cost-saving measure not uncommon in this region but seeming out of place here. Again, as the sunlight and its cheer vanished behind a slate of clouds, a bleak sense of foreboding overcame me. Winter was coming. I had arrived in Vermont one year before, almost exactly, early in what would become a long and oppressive season. This unfortunate recollection in that moment only served to deepen my interior darkness. This winter would be, must be, brighter. I shuddered deeply in the shade of the looming house then found myself racing back, retracing my steps through the weedy tufts and tangled burdock, hurrying to return to the warm den, the immediate heat of the wood stove. I’d found the answer to my question, which left me uneasy as I reentered.

There were no branches touching the house, no sign of disrepair. “What do you think of that, Buckwheat?” Her response was a reproachful silence. I distracted myself by filling a big bowl with the candy I’d bought for our trick-or-treaters, carving and lighting a jack-o’-lantern to sit on the steps outside the door, then unpacking clothes into drawers and preparing dinner. Halloween guests would be arriving at dusk as my husband returned from work. They would provide the link with the world I desperately needed after my first day alone in this house. I flicked on the driveway floodlights and set the candy bowl near the door in the den. I decided not to say a word about the strange knocking sounds or my panicked search for their origins. I hoped the noises would not be repeated, or if they were that I would have company there to hear.

But our first evening passed uneventfully, no noises, no trick-or-treaters.

News travels fast in a small town, I guessed. Must be the neighborhood kids were shy of strangers. As I snapped off the outdoor lights, I noted the first snowflakes of the season floating by. The next day the pattern repeated itself. As soon as my husband departed, leaving me alone with Buckwheat, my morning ritual was interrupted by the same, sharp, random, rapping noises. Sometimes they clearly came from the wall between the den and the laundry room, sometimes, muffled, from remote corners of the house, the front parlor or upstairs, both closed off to my exploration. Once again, Buckwheat responded with arched back, fur on end, staring fiercely in the direction of the offending noise. I was certain the sounds emanated from within the house, not from outside, but the deliberate staccato eluded detection. Just as we would relax, rap, rap, rap! would shatter the peace.

Not so much afraid as the day before as anxious, I felt more worn out as evening neared and decided once again to keep this to myself. Tomorrow was the weekend. I would wait until then, in hopes of having a witness besides Buckwheat to this unnerving occurrence. The next morning over coffee, I shared the news of the phantom knocking in the walls. I explained about searching for the source outside and inside our living space. “What do you think it is?” “Oh, like Jean said, just the sounds an old house makes, settling.” he replied. “I’d have thought this house was old enough to have finished ‘settling’ a long time ago,” was my response. His lack of interest irked me. “You’ll hear it today. You’ll see what I mean. Buckwheat hears it, too.” I instantly regretted sounding so defensive. Just by the wary look he shot at me, I realized my mistake. “What do you think it is?” he asked. Good question. “I don’t know. Not snow falling off the roof. Not yet.” My exceedingly rational husband was not picking up on my concern, at least not in the way I wanted him to. What did I think it was? I busied myself clearing the table, grateful for the distraction. As I washed up the dishes, my husband showering in the next room, I heard him say something indistinctly, behind the background rush of running water. “What?” I called. “I can’t hear you with the water running.”

More murmurs came through the muffling background noise. I turned off the kitchen faucet, grabbed a dishtowel, drying my hands as I made the quick turn out of the kitchen and pushed open the bathroom door. “What were you saying? Were you talking to me?” His puzzled face appeared from behind the billowing curtain mounted from the ceiling bracket over the claw-foot tub. “No. I didn’t say anything.” A long silence grew between us as I backed out of the room, pulling the door closed before me. The cadence of human conversation is unmistakable.

“Then who was talking?” I wondered aloud into the empty dining room.

Looking around for Buckwheat, for validation, I realized, I followed the vibration of her deep purr, entering the bedroom to the right of the front hallway. I knelt to pick up the bed skirt and there she hunched, not purring but growling, long and low. As I reached for her, she bared her teeth, hissing, and withdrew further, my comfort object lost to me. Of course, the quiet of our first weekend was unbroken by any disturbance. Day after day in the following weeks, waiting for the unwelcome sounds became as distressful as hearing them. It became increasingly hard to say goodbye to my husband in the morning, knowing how long my days would be as I endured the unwelcome interruptions to what should have been peaceful solitude. My household chores provided no distraction and little satisfaction. I rattled around the hours, waiting for my husband to return. But my unwillingness to again bring him into my confidence gave us little else to talk about and further isolated me. I had broached the possibility of getting a nine-to-five job in Newport so we could commute together, but perhaps because of the timidity of my request, on top of the scarcity of employment, I’d been encouraged to wait for a better time.

After all, the Scofields were counting on me to keep the home fires burning. This was my job. I should have been appeased but instead felt trapped. The constant, if erratic, interruptions had worn me down to my last raw nerve. “How long can this go on?” Just as the question entered my head, the rapping came again, this time from a distance, upstairs I was sure. My startle reflex by then had been tuned to hair-trigger sensitivity. I looked instinctively for Buckwheat, and then remembered. It had been weeks since she’d kept me company. I’d find her under the bed as usual. She didn’t even growl anymore, just glowered, coming out to eat at night when I slept, slipping along the edges of rooms in rare daytime excursions, her shunning my punishment for ever bringing her to this place.

Suddenly, I was angry! I’d enough of our cowering. I leapt to the door in the corner of the dining room, the one that led upstairs. The forbidden door. Lifting the latch, the door to a narrow staircase sprung open. Dismissing the guilty promise to stay off limits, I ran up to the second floor landing. The frigid hall was lined with closed doors. Starting with the furthest, seeking an unlatched culprit, I opened each with suspicion, yet no possible source of disturbance presented itself. I instead marveled at the immaculate rooms beyond, the girls’ bedrooms, one in the front of the house overlooking the road, one at the back reached as well by the back staircase leading down to the laundry wing, each room decorator perfect.

Nothing to account for the noise I’d come to investigate.

I retreated to the stairs I’d just climbed. One last door on my right remained, but on opening it, I gasped as blisteringly cold air enveloped me; I slammed the door shut, briefly glimpsing before it closed Jean’s sewing machine perched amid shelves filled with fabric and supplies over which I might ordinarily have lingered out of a common interest. In seconds, I was down the stairs, leaning hard against the door I’d breached mere minutes ago. There was no question of explaining this house and its “quirks” by logical means. Of course!

This house was haunted. Anyone who’s read or heard just one ghost story knows about the bone-chilling cold that accompanies the presence of ectoplasm.

Yes, the ambient air temperature upstairs was cold due to being closed off, but the ghostly aura is colder by far. All that I previously had experienced that could only be called otherworldly rushed into the space cleared in my mind by the horror of the moment. I knew a thing or two about ghosts. Almost everyone I’d ever met enjoyed the thrill a good ghost story provides, the dark place entered into willingly, knowing it’s “just pretend.” So many of us love the knife edge of fear, the mingling of disbelief with the faint hope that perhaps there really are such things, even as we assert there’s not. Being of Irish descent, I may have been raised inclined to believing in more than meets the eye.

My mother used to tell us stories she’d heard from her Uncle Jack about the ghosts he and my grandfather (who never admitted to any of it) had met on the family farm and byways of County Kerry as kids, before their emigration. I was never sure if my mother believed them, but she told them so well and so true to the last harrowing detail that I almost did. As a young girl I also had read voraciously and especially thrilled to reading ghost stories. The Irish are famous for their ghost stories, but the British and New Englanders seem equally fond of the genre.

I also found that spirits inhabit the belief systems of other if not all cultures around the world, from Scandinavia to Native America to Asia, and are featured in the legends and myths of traditional literature up through the centuries to contemporary fiction and supposed non-fiction. Of course, most ghosts were frightful; but many, like Wilde’s Canterbury Ghost, were comical, pitiable, and others were earnestly helpful to the stranded hitchhiker, the lonely trucker, those who seek to right a wrong or find what is lost. Almost all of these spirits, friendly or not, had met an untimely or tragic death, and many sought redress before they could be released from their limbo. Many fine writers seemed to have been fascinated by ghosts and by their shattering effect on the humans they visited.

There is an air of dignity and respectability about these literary stories that provides further endorsement of our mortal desire to believe in the possibility of life beyond death, in the absence of any real proof to the contrary. But for all my immersion in and great pleasure taken from reading about them, I, like many other people lacking personal commerce, never really believed in ghosts or haunted houses.

My first experience with a haunting was in an old farmhouse in the New Jersey countryside. A college friend, living off-campus, was very matter of fact about his ghost, the one that played with the electric lights, flicking them on and off at will, along with the television, the radio, even the horns and lights in the vehicles parked in the dooryard. I was witness to this display on one occasion, and as it was matterof-factly explained to be a routine occurrence, frequently observed by many farmhouse occupants and guests, I accepted this unusual assertion without question. Later, in the historic neighborhood of Sneden’s Landing on the Hudson, I visited in another home where all the clocks had stopped at exactly the same time, marking the drowning death of a boy who once had lived there, The proof of this eerie commemoration was visible on every clock face, left unchanged ever since by a grieving mother. The boy’s family and friends, one of whom was my husband, all agreed without a shred of fear or skepticism that this was verifiably true. I believed that they believed, and who was I to contradict? I recalled a song I learned in elementary school, “My Grandfather’s Clock,” how “the clock stopped, never to go again, when the old man died.”

And since moving to Vermont, I had been invited by friends living in a huge old farmhouse to check out the ghost of a woman who frequented their upstairs hallway, but disappointingly I had not been privy to her sighting. In their company, there was more exciting than frightening about their haunting.

Within seconds of this parade of memories, and maybe because I was warmed by them, when the next abrupt round of knocking came, rather than be undone by fear I felt my terror dissolve, replaced by fury with the Scofields. How could they invite us into this house without fair warning? “Snow falling off the roof!” my foot! I glared across the dining room to the closed door beyond which lay the forbidden front parlor from where the sound had just come. Fueled by adrenaline, I strode belligerently across the recently waxed floorboards, unlocked the door, and entered that room without a twinge of guilt or fear. The parlor looked so serenely composed I stopped short.

The formality of the overstuffed wing chairs and Victorian sofa, the fussy tables covered in lace and knickknacks, reminded me of the nineteenth-century novels I’d read where front parlors were reserved for socially constrained gatherings—Sunday visitors, courting couples, the laying out of deceased relatives. This room was in a state of preservation, an ode to earlier times. A low bookcase ran along the wall, and of course I was drawn to it. The titles caught my attention at once. With few exceptions, these were works of nonfiction focused on the occult and paranormal activity, Spiritualism, psi and psychic experiences, ghosts, poltergeists, “true” stories of hauntings—on and on, in reckless order, volume upon esoteric volume. I sat back on my heels, scanning the bindings then pulling one after the other off the shelves. Obviously, someone in this household was distinctly curious about life after death and was making a study of it. In triumph, I heaved to my feet under the weight of a stack of books I’d pulled to explore further.

As I turned to leave the parlor, an old photograph atop the round table between the front windows attracted my attention. Shifting my books to one arm, leaning in for a closer look, the sepia tone confirmed its age, as did the clothing worn by the three subjects, a woman and two men, one much younger, their son most likely. They stood stiff, riveted by the camera, stunned as if before a firing squad. Two trees flanked them, today two huge stumps barely visible in the grassy strip between the front porch and road. I did wonder who they were, what were their names, as I set the photo down carefully. Then I froze, as I saw what had escaped notice at first inspection.

There in the picture, in an upstairs window above the porch, the curtain was drawn back and a pale smudge, an indistinct face, gazed from the lower left windowpane. Who did this face belong to?

Why wasn’t this person in the photograph? My sympathy first aroused turned to suspicion then horror as I realized which room this was, the room at the top of the stairs, the freezing cold sewing room, the haunted room! Whose ghost lived there? The deep feeling of dread that had become my day-to-day mood replaced the sense of ease that had settled on me as I perused the bookshelves. Setting the photograph back in its place, hands trembling, I fled, clutching my treasure of books. Shutting the door firmly, turning slowly to face the dining room with its long table banked by matched chairs, I considered what all this meant. The secret library confirmed my strange experience. I was not crazy, nor was I letting my imagination run away with me.

This house was haunted, and I was not the only one who thought so.

In spite of my breach of trust, I was ready to confront my husband and the Scofields. For the rest of that day, I absorbed myself in reading about ghosts, poltergeists, and purportedly true visitations by myriad spirits abroad and at home. Again and again, the literally chilling effect that accompanies the presence of a ghost was confirmed, as were the rapping sounds documented in so many instances of haunting. These were commonly believed to be attempts at communication from worlds beyond. I also learned that sensitive young girls, especially, have been identified frequently as provocateurs of paranormal activity. Was I at twenty-one still young enough to call up a ghost? Sensitive? Yes.

With the turn of each page, I felt the power of knowledge dispel my fear and anxiety. By evening, I was no longer the listless, tongue-tied wife of that morning. I sprang to tell of my adventures in this house, upstairs and down, and of my amazing discoveries. Expecting to take him, in his shared excitement and interest, on the grand tour in spite of my lingering apprehension, I was struck by the mild skepticism in my husband’s expression mediated by patient tolerance in his tone.

Why, he wanted to know, had I broken our promise to Arthur and Jean? We weren’t supposed to go upstairs, or into the parlor.

These books strewn across the dining table had not been made available to us, and the Scofields clearly hadn’t wanted us reading them. Maybe they were interested in unusual subjects, but that didn’t mean their house was haunted. Did it? In the face of his calm assessment, reinforced by the fact that he never once had heard the rappings or the sound of voices in other rooms, what could I say? After insisting that it could do no harm to read a book then return it to its shelf, I said no more. Without his firsthand experience, how could I expect him to understand?

The next morning, however, just as soon as the door closed behind him, the knockings began again, interspersed with the murmurings of a conversation engaged in several rooms away. Off shot Buckwheat to the bedroom, she who had ventured out to the den the night before to keep me company in the strained silence. Resigned to my situation, I kindled the parlor stove to revive the coals, lay on a few logs and stubbornly settled in to my books, immersing myself in my quest to learn and so overcome my fears.

It was fascinating to read what so many reputable others had been researching and pondering so long ago. I felt myself opening up to a new perspective on the events in this house. Hours passed as I read on. If the disturbances continued after I picked up my books that morning, I was unaware of them. Time had been moving so slowly in the first few weeks in this house but now was speeding by. All of a sudden it was time to make supper again. Where had the day gone and what had I accomplished beyond my occult studies? I hadn’t done a bit of housework in two days and it showed. Guiltily, I watered the drooping houseplants and swept the kitchen floor. I really was falling down on my job.

That night we made small talk; there was no profit in sharing all that I had wondered about that day. “Why borrow trouble” as my Grandma used to say.

Thankfully, a co-op dance was planned for the weekend. We would get together with friends making the trek down to Glover from points north. Company, finally. Energized by planning for the weekend, I was distracted from the events that had previously unnerved me. Cleaning and cooking seemed to insulate me from the unwelcome presence that continued to make itself known only to me. As I dusted and polished, I turned up the stereo, determined not to succumb to the raw fear that never quite receded no matter how familiar the peculiar had become. In spite of my studies in ghosts and other occult activity, which by now encompassed nearly every volume on the shelves, I couldn’t shake the worry that my mind was playing tricks with me, as I believed my husband’s cautious gaze implied when he thought I wasn’t looking.

Our pre-dance dinner proved a welcome opportunity for conversation and laughter that had been so lacking for a month now. Our friends marveled at our deluxe digs and accepted the boundaries the Scofields had set on the exploration of off-limits corners of the house. Everyone understood about the price of oil in those days. I never considered relating my weird experiences in this house or speculations as to their cause. I’d had enough of raised eyebrows and bemused glances.

We walked up to the town hall through our first real snowstorm of the season, dense, tiny flakes accumulating quickly.

As we reveled, the snow fell steadily beyond the doors of the town hall. By the time we left for home, there was a foot or more of snow piled on top of every vehicle, requiring much sweeping and more shoveling to clear a way onto the road before the drive home could commence. We were glad to be walking and offered others the opportunity to do the same, leaving their buried cars to deal with in the morning.

One good friend, having no home fires to tend, accepted my invitation to spend the night on the couch in the den. How amazing then, when my husband offered him a bed upstairs for the night. His concern for the well-being of others, a quality I admired greatly in him, had trumped whatever objections he had expressed to me about overstepping the boundaries the Scofields had set. He led the way upstairs; I hung back. I could hear them laughing, joking about the décor in the girls’ bedrooms. Our friend chose the back bedroom, the one that also accessed the back stairway to the laundry wing below. More blankets and quilts were supplied to combat the chill of the unheated room, and goodnights said.

As we entered our darkened bedroom, Buckwheat’s customary grumbling offered small comfort. She was my only ally in this strange scenario, privy to the same supernatural goings on I lived with every day.

I fell asleep before long, for how long I don’t know when I startled awake to the sound of boots taking the stairs two and three at a time, beating a hasty retreat! I listened as our previously stranded guest fired up his buried car, tires slipping and spinning against lost traction. I watched from the window as red taillights dimly, rapidly disappeared north. Guessing at what had just happened, I smiled, returning to bed to sleep peacefully in the belief that I had another witness, a human being this time, who had shared in the secret this house held.

The next morning I shared my suspicions about our friend’s abrupt departure with my husband. To my surprise, he allowed for the first time that our friend might have responded to something weird about this house. Yet he was still not the least inclined to move out. I would learn to live with it, he assured me.

Free rent was free rent, and a promise was a promise. We couldn’t let the Scofields down. We couldn’t leave the house to freeze. And no, we couldn’t contact the Scofields as I wanted to, to see what they knew about this “haunting.” They’d think we were nuts, and even if we knew we weren’t, we couldn’t afford to tell them what I suspected. Much later, I asked our friend what had become of him that snowy night. “It was so cold. You never turned the heat up!” he accused. “And the bed, it was a bundling bed. So uncomfortable.” I had to ask about that. “A bundling bed?” “You know. Back long ago, when people came to visit, they slept in bundling beds, with a board down the middle…”

I remembered learning what a bundling bed was, and the act of bundling, but there was no bundling bed in the upstairs bedroom. What was he talking about? Had he been dreaming? “And then you were knocking on the door, and hiding when I opened it. You did that three times!” At this point, he had left, preferring the wintry highway to the strange arrangement he found himself in that night.

Disappointed, I realized that while he had had a similar experience to me, he did not construe the same meaning from it. A ghost, apparently, had never entered his mind. Resigned, feeling helpless to change my circumstance, I was stuck in this house in an increasingly tenuous relationship.

Stubbornly, I continued my study in the paranormal. I was ever more struck by the frequent connections made between ghosts and children, ghosts and young women, and ghosts and certain common household objects, particularly clocks. As a means of communicating between earthly and unearthly planes, across dimensions of time and space, clocks provided what spirits needed, a way to make themselves known. The clocks in the house on the Hudson made sense to me now. The incidence of rapping or knocking showed up in my reading, too, time and again, as a means of ghostly communication. And while the Spiritualist movement of the late eighteen-hundreds proved to have had its share of frauds and shysters, there were too many instances when the validity of the rapping could not be debunked, neither could numerous other inexplicable documented sights, sounds, and sensations. I did take comfort in this revelation; however, the knocking in the walls and the murmured tones in distant rooms continued to interrupt my thoughts and daily activities and raise my hackles.

More than ever, I was a bundle of frayed nerves. Mundane routines of the day provided little comfort to me. In the last weeks of November, as I was dusting and polishing the dining-room furniture, I reeled, horrified to see a scratch in the broad, smooth surface of the table. I had by now polished this lovely piece many times and knew its grain well. A scratch? How could this be? I turned on the overhead light to cut through the gloom and leaned closer, applying more polish and pressure as I attempted to erase the awful defect. It seemed only to come into sharper relief as I bent to examine the scratches, which definitely had not been there the last time I had cleaned.

In disbelief, I made out letters awkwardly etched into the tabletop, as if by a child with an unsteady hand: H-E-L-P M-, the last E incomplete, trailing away as if the writer had been interrupted, or overcome? Help who? Was someone trying to communicate with me? How could this be happening?

I was out the door and running up the road, struggling to put on my coat in the freezing afternoon before I knew what I was doing. What was I doing? What would my husband say, or Mrs. Scofield? Who would believe me if I said I wasn’t responsible. I went straight to The Busy Bee, sitting down to the counter before realizing the prim-mouthed proprietress was just getting ready to close for the day. “Any coffee left?” I faked, and gratefully accepted the last of the pot from the reticent woman behind the counter. “Phone’s not working,” I lied. Turning to the payphone on the wall by the door, I called my husband’s workplace and pleaded with him to come home early.

Unable to linger, I returned unwillingly to the house. By the time he made it down to Glover from Newport it was nearly dark. I had let the fire dwindle, but the chill in the dining room had nothing to do with the indoor temperature as we stared down at the table in silence. I realized what he was thinking. “You think I did this?” and even as I asked, I wondered, “Would I? Could I? How else, really, could this be explained?” Nothing I had read made mention of ghostly graffiti or vandalism. My recently acquired confidence swept away in an avalanche of misgiving. I felt the rift between us widen. No matter that a mutual friend had recently, if unwittingly, confirmed the unwelcome presence that had plagued my existence in this house since the first day. My husband had not witnessed any of it, so to him it was not real. I again began to doubt my own senses. We replaced the protective covers we always used when we ate at the table, draped a tablecloth, squared it and turned away.

Our supper was a can of soup in front of the TV. There is no lonelier feeling than to feel alone with someone you care for. I think we both knew the feeling that night. Fortunately, justice was swift. I went to bed early, Buckwheat encamped behind the bed skirt; I woke to the sound of a late-night talk show, so it must have been nearly midnight. It was snowing and blowing mightily outside, curtains moving slightly in the gusts sneaking in around the trembling window casings. As my husband sat propped against pillows watching television, back to the wall between our bedroom and the front hall, a loud knock resounded at the front door, the door no one ever used. “Must be someone broke down in the storm,” and I watched as he made his way through the dining room into the den and out of my line of sight. I listened as he opened the door to the driveway. “Hello, hello? Come on around,” I heard him call into the night, into the wind. Simultaneously, I heard through the wall behind my head the sound of the front door opening, then shutting! Deliberate footsteps sounded, walking down the hall toward the dining room.

By this time, my husband had returned to stand where I could see him from bed, in the doorway between the den and dining-room, staring up the hallway to the front door, obviously listening to the same sound of footsteps I, too, was hearing. As I continued to stare at his dumbstruck face, he stared fixedly ahead as measured footsteps turned and retreated back up the hall; then distinctly, impossibly, we heard the front door open and close. Trance broken, my husband raced up the hallway, throwing the bolt, locks and security chain to open the unwilling door.

Out on the porch then, I heard, “Hello? Anyone there?” I knew without seeing for myself what he would soon tell me. There was no one there. No footprints in the freshly fallen snow on the porch or the ground beyond. No one had been there. No living person.

He reentered the house, carefully shutting the door, resetting the lock, the bolt, the chain before retracing his steps down the hall and turning to stand in the bedroom doorway. Slumped, defeated, he now knew what I had known for what seemed like forever. His first was the most dramatic encounter so far, and I felt for him. I had had the advantage of a more gradual buildup to this climactic event. “Now you believe me? I asked, shaken but so relieved. Then, “Now can I call Jean?” “No!” he insisted, weakly adamant. “We said we’d be here until spring. We’ll just have to live with it.”

In an overt act of rebellion, the next day, I wrote to Jean. I explained, most apologetically, that we had had some unusual experiences in the last month—the knockings, the murmurings, the midnight visitor. Within days of posting my letter, I received her response. “Yes, it’s true,” Jean wrote. “We had hoped you wouldn’t be bothered. Things quieted down after the girls moved out.”

They, too, had heard the rapping and experienced other strange sensations. It had all started after they renovated the mudroom and summer kitchen in the back wing to create the laundry room, a process Jean thought might have provoked the visitation.

“Call our daughter, Alice. She lives in Montgomery. I’m sure she’d be happy to come down and tell you all about it.” Jean had included Alice’s phone number, so I called immediately. My invitation to dinner was readily accepted. Alice seemed eager to share their story. Soon we found ourselves sitting around the dining table, Alice comfortable in her home and yet a gracious guest. She was beautiful, vivacious, and magnetic with the confidence many beautiful women exude. She was only a few months older than I was but seemed much more worldly. I marveled at my husband’s intense curiosity for Alice’s account. The supernatural presence within the Scofield home was a topic he had not engaged in so wholeheartedly with me. I may have felt a passing jealousy, but I, too, thought Alice was fantastic, most of all because she confirmed in such a disarming way all that I had come to know about the house and its inhabitants.

Alice explained about the laundry room, how the ripping and tearing to create that room behind the den seemed to instigate the intrusion. The back wall of the den was the place the Scofields and I first heard those jarring rap-rap-raps. Alice and her sister also had had invisible pranksters knocking at their bedroom doors upstairs and had felt the bitter cold emanating from their mother’s sewing room.

Alice explained that Jean had developed a passionate interest in the occult and had built quite a library of books if I was interested. I avoided my husband’s eyes. At this point I had to confess all of my transgressions, the broken promise not to trespass here or there, including reading most of the books in Jean’s collection. Alice did not seem perturbed by this, if anything, sympathizing with how difficult it must have been to spend so much time alone in this house with no one else to witness these encounters. Jean had always had Arthur right there, his company and support, and the girls, too.

They had never really felt fearful or even upset, apparently, only curious, bemused, fortunate. I marveled at their resiliency and courage. Was it easier for the family to deal with, knowing they were all in it together? Is that what made it all not so much scary but rather unique and fascinating? The time came to show Alice the table, etched with the spooky, shaky plea for help. This was startling to her, but again she seemed more sorry that this had occurred on my watch, reassuring me that her mother would perhaps be delighted that she had yet another bit of evidence of the visitation from beyond the veil.

I also brought her to the photo in the front parlor, and Alice explained that the photo had come with the house; she had no idea who these people were except to agree they must have lived in this house at one time.

When I pointed out the blurry image in the upstairs window, she peered closely, never having noticed it before. Yes, maybe it was a face. We wondered why the photographer would have left someone out of the picture. Or had the family? And wasn’t that the sewing room window? At last, her stories all told, we said goodbye. It had felt so good to hear her verify my experiences and also to learn that Jean would not condemn but understand why I had searched beyond the boundaries they had set for us in our own best interest.

Maybe I could begin to appreciate what a fortunate mortal I, too, was to live with a real live ghost.

In coming days, I attempted to make peace with my situation, but my anxiety in anticipation of the next communication from our ghost still inspired the same degree of agitation as in our first encounter. Jean and Arthur had had each other and their girls to cushion the shock, but here I was alone each day with no one to comfort or encourage me. Even though my husband was now a believer, his stamina in the face of this unearthly presence was not being tested, as mine was every moment he was away. In fact, that night in the hallway was his only encounter with our ghost, ever.

My dilemma was simple. I couldn’t move out and I couldn’t stay alone. A job would provide the only solution. But with limited previous experience, no car and two years short of a college degree, my options were limited. In this frustrated state, I awoke one morning, not knowing it would be my last day in the Glover house.

It was now the darkest time of year, and every light in the den could not brighten my mood as the snow continued to flurry past the windows. As usual, the knocking started up almost immediately in the den wall behind the couch, where I sat crocheting, the wall adjoining the laundry room where Alice had said it all started. Turning the stereo up, I kept busy with my handiwork, humming along to a favorite tune, “But every morning, I wake up and worry, what’s gonna’ happen today? You see it your way and I see it mine, but we both see it slipping away.” I broke out in goosebumps as I realized how uncannily the lyrics reflected my own situation.

Just then the lights went out, the music died. The power was down. In the dim light, I could see Buckwheat crouched by the door to the kitchen, staring up at something, her menacing growl reverberating.

Stepping forward to stand with her, I followed her gaze to the kitchen clock on the wall opposite us, a bright yellow electric clock, the cord plugged into an outlet beneath. Freakishly, the hour and minute hands were spinning madly around its face, faster than time would allow. In silence, I stepped forward, grabbed the plug and yanked it out of its socket. With cord in hand, we stared as the clock’s hands continued to whirl. There I went again, as I had only weeks before, out the door and up the road to The Busy Bee, which though similarly without power seemed so much more inviting.

Using the pay phone, I again called up to Newport, under the hard gaze of the proprietress, every customer listening in carefully though their backs were turned to me. As steadily as I could, I explained the situation and said I’d wait at the diner, I’d not return to the house alone.

I sat at the tiny counter, drinking coffee in the quiet I knew had settled on the regulars as soon as I had entered and which would be broken as soon as I left. My husband arrived and we returned together to the darkened house. Poor Buckwheat was right there where I’d left her, but of course the hands on the clock were still. I can’t remember at what time they had stopped or if I even thought about it. All I knew was my time was up. We had come to an impasse we seemed unable to move beyond together. I presented my ultimatum; he could come or he could stay, but I was leaving.

We looked to each other across a broad gulf of difference. It was unsettlingly calm, eerily anticlimactic. We were both determined. He would not go, duty bound to the contract we had made, unable or willing to consider an alternative plan. I could not stay. Without anger, deeply saddened, we parted ways. In no time, I rented a tiny third floor turret apartment in Newport in what looked like it should have been a haunted house but wasn’t. “No Pets” however, meant Buckwheat could not come with me. She had to endure what I could not, and I felt bereft and guilty about that. I hoped that in my absence, as had happened when the Scofield girls moved out, things would quiet down, and her final days in the house would be undisturbed. They stayed together in Glover until late April when Jean and Arthur returned, and then moved on.

Our paths crossed only occasionally after, though always amicably. My first jobs, in local bars and restaurants within walking distance, called on my cooking and baking and social skills, leading to secure employment and greater opportunity.

As time went on, I heard numerous other accounts of local hauntings, which I have come to recognize as common trade in these parts. I took interest in their telling but remained reluctant to revisit my own experience.

Gradually, unexamined, that phase of my life receded in the rush of day-to-day. In the intervening years I remarried, tended to my family, and completed my bachelor’s then master’s degrees, and finally my teacher certification. In 2000, I embarked on my new career path with great commitment to the role of literature in learning. And so I began to tell my story to a captivated audience of open-minded adolescents who accepted my tale with as much compassion as gleeful horror. “Tell it again!” and again and again they would beg. And since I looped with my multiage classes for two years, they did hear it twice, always insisting it was better the second time. This was a lesson they adored. In our dissection of the story, we mapped each scene on the arc of our story map.

The exposition and rising action involved my move to Vermont and eventually to the Scofield house, with the first inklings of the haunting.

The crisis evolved, as I alone became the haunted, the plea for help in the tabletop a hair-raising crisis. My husband’s only encounter with the ghost in the hallway fit the climax, the Scofield’s confirmation comprised the falling action, Alice’s visit the provided resolution, and the episode with the clock and my ultimate departure the denouement; it all fit perfectly. Together we identified other narrative elements— setting, protagonist, antagonist and allies, goals, motivations, and theme. My students were masters of the takeaway and this is where my deeper understanding of this chapter I’d considered closed for so long began to emerge.

As happens so often, I learned as much or more from my students as they did from me. In my earliest narration, I omitted the part about leaving my marriage in deference to their innocence and my right to privacy. My conclusion, however, was clearly unsatisfactory, and they wormed the truth out of me eventually, asking pertinent questions about what happened to me, to Buckwheat, to my husband. Divorce was part of their world growing up, and my own barely raised an eyebrow. What had seemed an impossible ending to me struck them as inevitable. This personal disclosure bumped our level of discourse to new heights. Before this revelation, they offered accurate but comparatively mundane thematic lessons: “If it looks too good to be true, it probably is” and “Things are not always what they seem.” Now the themes they discerned were more universal and profound: “Stand up for yourself even when you stand alone” or “Believe in yourself,” and “Sometimes your self is the greater good,” an ironic twist on “Self versus the greater good,” a universal conflict which runs like a thread through so many great stories.

They decided that since the promise to care for the house had been made under false pretenses, we owed nothing to the Scofields. Of course I had every right to leave. I had no recourse but to save myself.

How stunning to hear from them that I was mistaken, the antagonist in this story was not the ghost, but anyone who would refuse to believe me or to understand the intolerable circumstance I was required to live within. The ghost, my ally, had helped me to move on with my life, go to work, become independent, make new relationships and discoveries that had brought me to them, my students. It was fated that I should have met opportunity in such an unlikely situation. Who knows where I’d be if not for that well-meaning ghost I had so miserably misunderstood all those years! Always, the lesson would end with my students’ sharing of their own tales of the supernatural, many much more frightening than mine.

They felt safe in that space I’d created to tell the stories in public that they may have hesitated to tell before, not wanting to be laughed at or disbelieved. Then they would demand to know if I’d written mine down, and why not? After all the writing I required of them, it was only fair. I would promise to get to it, yet never did. Years passed, and I continued to run into former students and their parents (the kids always running home to share around the dinner table that night) who would always reminisce about the ghost story and wonder if I’d written it yet. And I would have to admit, “No, not yet.” I did begin a draft in 2004, but as it turns out, this story had not finished telling itself.

Naming the Ghost, Part II: The History

In truth, this story might never have come to print if not for my chance encounter with Joan Alexander, the Glover, Vermont, historian and aunt to two of the many students who thrilled to my bone-chiller. “I hear you have a Glover ghost story,” she informed me on our introduction at a local charity event for which we were both volunteering. “Which house is it?

Do you have any idea who the ghost is?” “What? How could I know?”

Startled, unaccustomed to speaking with grown-ups, much less strangers, about my secret, I was on the alert but curious. Joan explained that I could look it up. Look up the house, who built it, who lived there, and died there. I could figure it out. “I’m working with a boy in Barton right now, helping him research his house. He says it’s haunted, too.” In all the years since my encounter, it had never occurred to me to try to name my ghost. There I stood, staring at her, realizing she could help me answer the question I’d never thought to ask.

As a historian, she had access to and was intimately familiar with the town records of Glover, Vermont. “Births, deaths and marriages, land records, cemetery records,” she reeled off. “You can look it all up. Online, too. There are websites.” Joan was so matter of fact, I found myself quickly agreeing to meet with her, though it took a few months to finally summon the grit it took to call her, to bring into real time what I had consigned for so long to my past and flirted with only as a lesson in my classroom with the most avid of audiences.

In search of the Vermont ghost origins

Our appointment at the Glover Historical Society was finally secured, and there began the next chapter of my story. Even as I drove to Glover, I worried what on earth I was up to? Why was I doing this? Would it be worth my time or trauma to revisit? Did I really want to know more or risk learning there was nothing to know? After all, I was a very different person now, with other pressing concerns. Before I turned up the hill to the Glover Town offices, I drove slowly by the house I’d briefly lived in nearly forty years before.

How many times in all those years had I driven past that house on my way through Glover, slowing down but never stopping?

Only the paint color ever changed; the tidy porch and curtained windows maintained the same respectably benign front. I never saw anyone outside, or I might have followed my impulse one of those days and pulled in the driveway. To say what? “Hi. I used to live here a long time ago. Is your house still haunted?” Yet here I was about to do what I’d always been too scared or embarrassed to consider. I was going to find out if there really are such things as ghosts, or more to the point, if I could prove there was such a thing as my ghost.

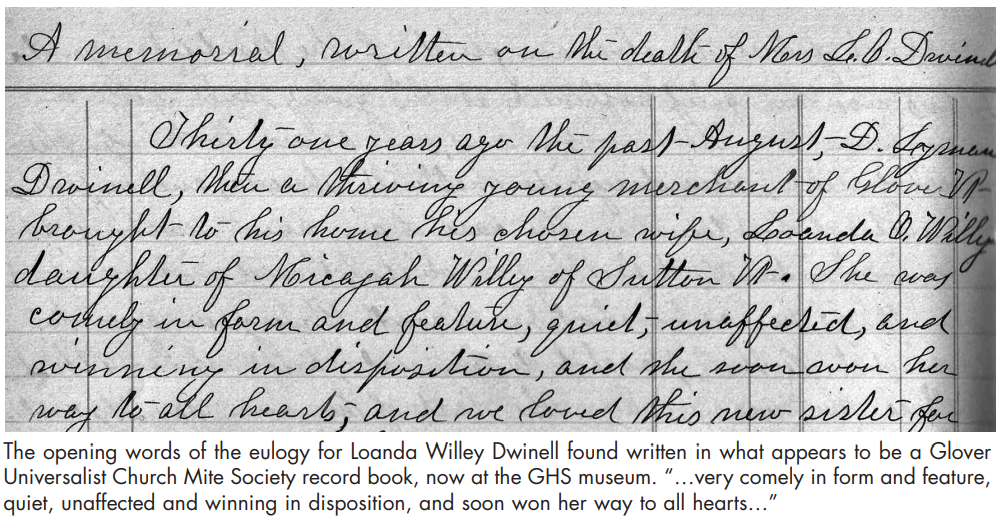

Entering the town offices, which also housed the Glover Historical Society and library, I took a giant step forward into the past. The town clerk generously welcomed us, making way to the vault that really was a walk-in safe, housing shelf upon shelf of leather bound ledgers, most of them exceedingly old but in an excellent state of preservation. The creamy pages of these mammoth books feel more like cloth than paper and are covered in a scrawl of blue ink faded to purple, painstakingly inscribed over a century ago by Glover’s proudly literate civil servants. I’ve read about this “spidery script” but never appreciated how arduous must have been the task of documenting the daily life of a town or any other civic business in need of recording.

A bank of card catalog drawers occupied one corner shelf, each drawer crowded with cards of various colors, on which family names and birth, death and marriage dates had been transcribed from the ledgers. A narrow table stood in the center of the vault, upon which one could lay the heavy books to peruse their pages without harming them. There was room enough for us to wander about, though we had to keep our coats on to keep the creeping cold from settling upon us.

Armed with notebooks and pencils, Joan quickly demystified what had seemed an impossible process. Start with the card catalogs, she instructed, look up a name and see where it leads. Find the number of the related birth, death, and marriage ledger with further information on that individual being recorded therein. How marvelous to realize that history is so directly accessible centuries later, that you can literally put your hands on it. These records, in combination with online resources such as ancestry.com that I later turned to, provide an overwhelming amount of data. I delighted in the puzzle of teasing apart the many names and dates, so many life stories mingled and layered together. To find those I was seeking seemed complicated, yet, fueled by my intense curiosity, it was amazing how the life stories of those who had lived so long ago leapt off the pages. How immediate their personal histories were to me.

How quickly I became intimately involved with folks I’d never met … or had I?

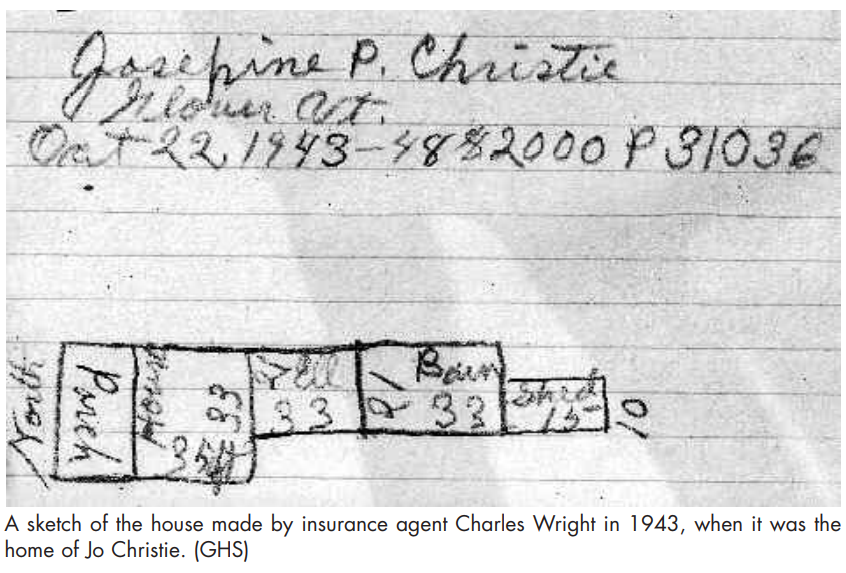

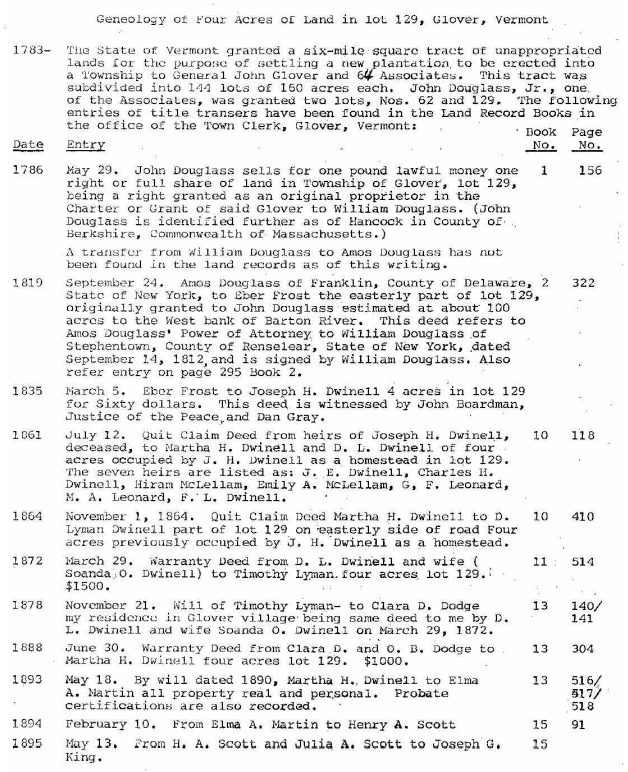

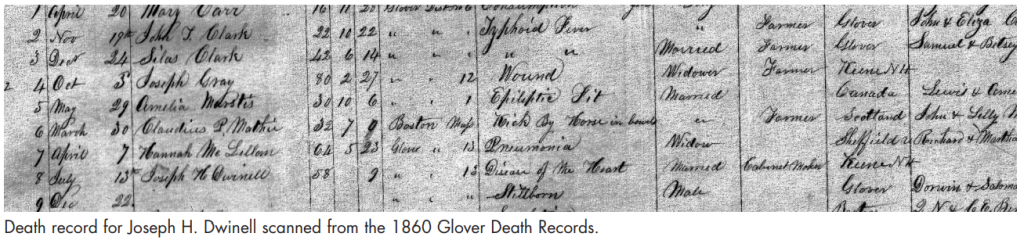

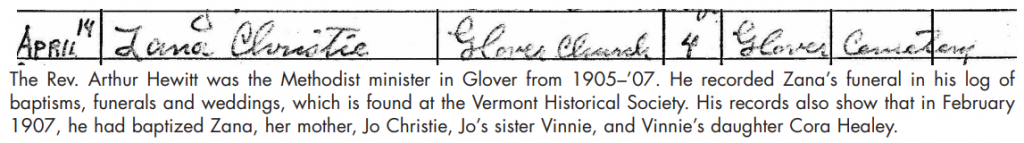

The first effort to document the line of ownership of the Scofield house, as I still called it, had been made by Richard Evans, who had purchased the house from Jean and Arthur in 1976, just seven years after the Scofields bought and restored their home. Mr. Evans’s “Genealogy of four acres of land in Lot 129, Glover, Vermont,” acquired through his research in the Glover land records and provided to me by the historical society, reveals nothing more specific of the lives of former owners than their names but proved the keystone for all further research. It was with this document, provided by Joan to me, that I entered the vault. In no time, I was navigating the space independently, starting with the first name on the list of many past owners, Joseph H. Dwinell.

It was here I first reckoned with the conundrum of historical research—the spaces between the hard data, where the intimate details of people’s lives remain elusive and which inspire the imagination. These spaces call out to be filled. I could not ascertain when Joseph H. Dwinell arrived in what is now the village of Glover in the town of the same name, traveling through the vast northeastern Vermont wilderness, up from Keene, New Hampshire, where he was born in 1802. Joseph appears to have befriended Timothy Lyman Jr., a farm boy born in Glover in 1805 whose name recurs in the genealogy of Lot 129. In reading of the earliest days in the town’s history, I learned that Joseph’s first trip to Glover was as one of the teamsters who drove the heavy wagons loaded with supplies and goods necessary to begin construction of the first permanent buildings in Glover.

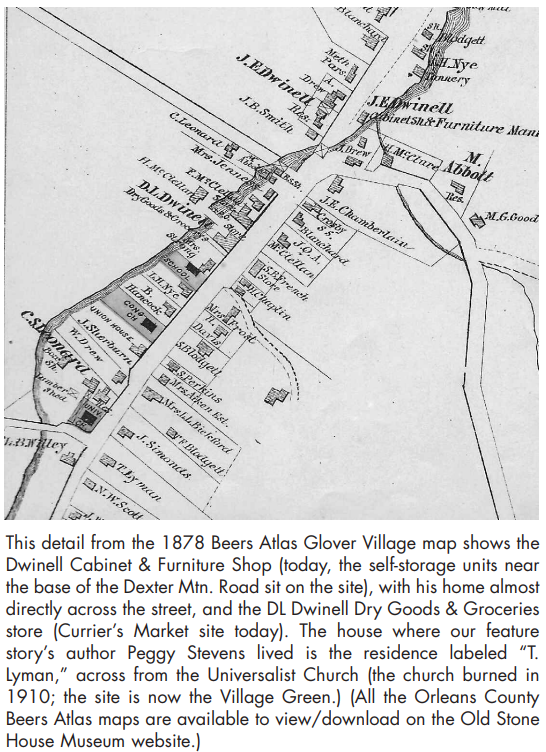

These buildings included Eber Frost’s homestead, the first house built in Glover Village, in 1820, and still perched midway up the eastern slope in the heart of the village today. As well, The Union House—today a nursing home, a tavern and stagecoach stop then, first owned and operated by Dan Gray—still stands on its original site close upon what was then and is now the main road through the village. Eber Frost, with his purchase of Lot 129, “100 acres to the West bank of the Barton River” in 1819, can be considered the founding father of Glover Village in the township of the same name, granted in 1783 to “John Glover and Associates” by the state of Vermont to veterans of the Revolutionary War.

Runaway Pond

The dense cedar swampland was no draw for John, nor for his descendants, who sold their shares to the hardier visionary, Eber Frost. By then, what had been useless swampland had been made more habitable by the change in the landscape caused by the fabled Runaway Pond, which filled the swamp and created a bed for the road that soon would find its way. Eber must have seized his opportunity to make the most of this advantageous, if accidental, turn of events. (The destruction, wrought unwittingly in 1810 by miller Aaron Wilson, came about in his effort to divert waters from Long Pond, five miles south of his gristmill, just south of the former cedar swamp where the village sits today.

The legend of the resulting catastrophe is still told and well-known locally, as the escaping lake waters channeled through the valley, creating the roadbed of Glover’s main street, what is now Route 16, and depositing deep layers of silt that became the fertile Barton River valley farmland between Glover and Lake Memphremagog in Newport, more than twenty-five miles north.)

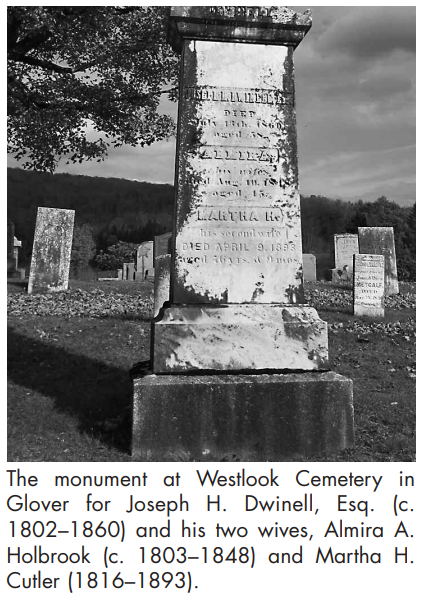

Joseph H. Dwinell must also have liked what he found in the Barton River valley, most of Glover’s earlier settlers having chosen to farm on higher ground in the surrounding hills. With his wife, Almyra Holbrook, also of Keene, Joseph built his homestead in 1835 on Lot 129, deeded from Eber Frost in exchange for sixty dollars, a lot not far south of Frost’s homestead and across the road from and just south of The Union House, whose proprietor, Dan Gray, witnessed the deed. Joseph and Almyra had established their family by then, six children in all. Further research revealed that Joseph carved out his cabinet-making business about a half mile up the road on the banks of the Barton River, where his craftsmanship was often applied to coffin-making, for the very young and relatively young by today’s standards, as well as for those community members hardy enough to live into their old age.

The vital records maintained in the chilly vaults of the Glover Town offices reveal daily tragedies, many infants lost to loving parents or parents taken from their abandoned children by diseases and afflictions we consider to be serious yet not deadly today. Almyra Dwinell passed away in 1848, according to cemetery records, but the cause went unrecorded at the time. She was the first Dwinell to die in the house and the first to be buried in the family plot in Glover’s Westlook Cemetery. Almyra left behind her widower and six children, and how hard that must have been for all of them, including Almyra. Was this reason enough for her spirit to linger, I found myself wondering? The 1850 census, conducted two years after Almyra’s death, registers the members of the Dwinell household as Joseph H., then forty-eight and a selectman in town and representative to the Vermont legislature in his second term, as well as his daughters Emily, twenty-four, and twenty-two-year-old MaryAnn, and their two brothers, Franklin and Daniel, aged fifteen and twelve. Sons Charles and Joseph E., who were present in the household at the 1840 census, had left home by this time. Oddly, several other names were listed as residing there in 1850, five members of the Leonard family and two young Smith girls.

Had Joseph, as selectman and overseer of the poor, taken in these folk out of charity or obligation as was the custom when it came to caring for the indigent? What misfortune had befallen them to require this necessity? I pictured the walls of the little house straining to contain these numbers.

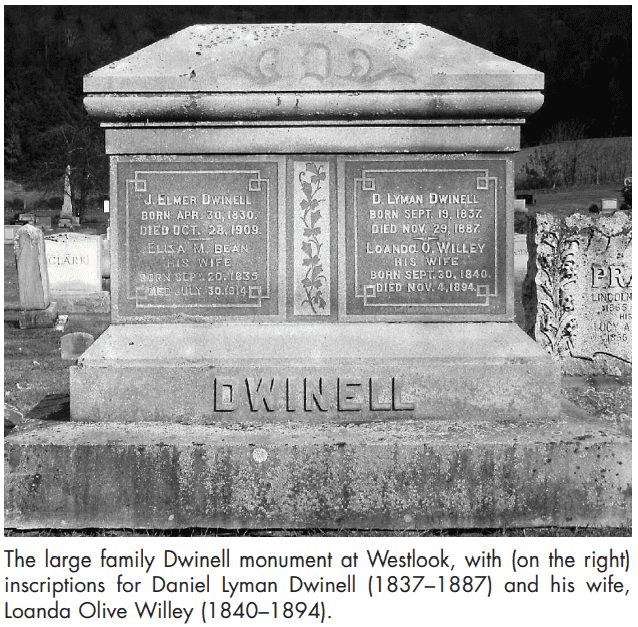

Moving on, I discovered Charles Dwinell’s marriage to Lois Cutler of Glover in 1857, recorded in that year’s birth, death and marriage ledger, and two children born to them, but this was the last trace I could find of him. Joseph H.’s namesake, Joseph E. Dwinell, at nineteen years of age in 1850, had returned to Glover by 1856, having married Eliza Bean of Glover in that year. They brought up their family in Glover Village, only five out of ten of their offspring surviving infancy. Young Joseph eventually took over the Dwinell family furniture business, evidence of which undoubtedly remains in local homes, antique shops, and rummage barns today.

Fueled by an intensifying degree of curiosity, and with the historical society’s assistance, I was using online resources as well as town records, amazed how easily these references to those who’d lived so long ago could be called up again. How immediate their history and how quickly I became closely involved with people I’d never heard of before. I did a quick search to see what I could find out about son Franklin, who had disappeared after the 1850 census. Young Franklin had left Glover in his late teens for greater Boston. I discovered him in the 1860 Somerville, Massachusetts’s census, a bookkeeper for a textile firm. By 1880, he resided in nearby Brookline, his occupation treasurer of a manufacturing company. He had married Alice Gould but remained childless. If he ever returned to Glover, I turned up no record.

The situation at the senior Dwinell’s home had changed yet again by the1860 census, with daughters Mary Ann and Emily, whose sweet voices had graced their choirmaster father’s Sunday choir in the Congregational Church just across the road from home, having married as well. Emily could be found living in Glover, with her husband, Hiram McLellan, farmer, and their three children. Mary Ann had married George Leonard, “mail agent,” and had moved with their three boys to Newport. The sole inhabitants of the Dwinell homestead then were Joseph senior, his second wife, Martha H. Dwinell, and youngest son, Daniel Lyman Dwinell.

Were these the people in the photograph I had found in the Scofield’s front parlor?

The period seemed right and the subjects matched the census—father, son, and stepmother. But whose was the face in the upstairs window? I wished I could lay my hands on that photo to look more closely and wondered what had become of it. What I had learned by this time was that it was not at all unusual to find these faces in the attic windows of old photographs, whether they be of invalids, hired help, or any others unable or uninvited to join the formal group photograph. So many faces and identities, recorded yet lost to history.

Dipping back into the 1850 census, I found a Martha Howard from Canada living with the William Cutting family in Greensboro. Jumping forward to the 1870 census, I found Martha Dwinell living with Asa and Hannah Taft of Glover. How had Martha come to know Joseph and to marry him, and why had she disappeared from the Dwinell family homestead within ten years of that photograph? Returning to the card file, there was the death record of Martha Howard (Cutler) Dwinell, but no record of her marriage to Joseph. I had to wonder why they had chosen to marry out of Glover, but no answer was forthcoming. My head was spinning by this time.

I had only been at it a few hours and already acquired so much information. By now, I knew what had become of Almyra and Joseph H. Dwinell’s children, more or less. Yet I had more questions than answers. First among these was why was second wife, Martha, living with the Tafts in 1870 and not in the Dwinell homestead? Then I realized that Richard Evans’s genealogy of Lot 129 held the answer. In 1861, the deed had passed to youngest son, Daniel, and to Joseph’s widow, Martha. Joseph senior had died of “bilious fever” in 1860, within the year of that census, the second Dwinell to pass away within those walls.

So son Daniel and Martha had lived on there together, Daniel marrying Loanda Willey of Glover in 1863, and soon after, in 1864, Martha quit her claim, leaving Daniel sole heir to the house. Two women under the same roof, one a stepmother- in-law, might not have worked any better then than now. I found myself wondering just what the relationship between Almyra’s children and Martha was like. Did they resent or accept her presence in their mother’s home? And how about Almyra? I couldn’t help but include her spirit in this unfolding drama. How did Martha’s presence sit with her?

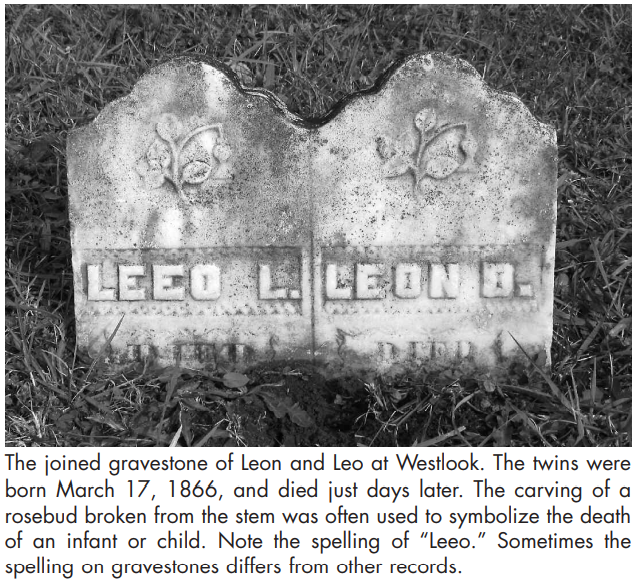

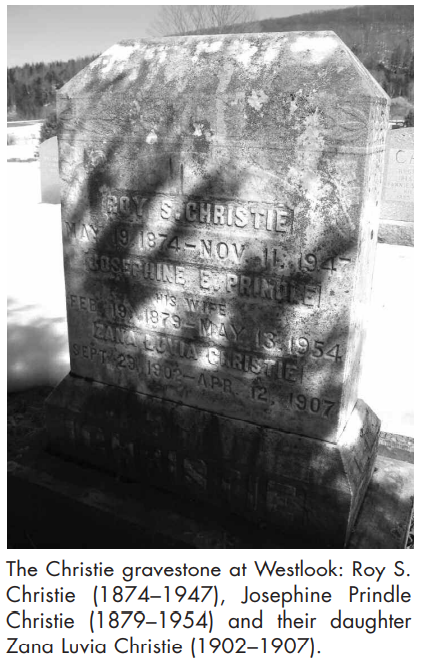

Referring again to the card catalog, I learned that Daniel and Loanda had celebrated the birth of twin boys, Leo and Leon, on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day, in 1866. Then, tragically, their deaths from influenza are recorded within three months; these little boys were the first children to die in the house. Poor grief stricken Loanda and Daniel never had another child; their loss must have been insurmountable.