Clarence Morse – “Good Money in Bad Times”

by Scott Wheeler

“Bootlegging was risky business,” says ninety-one-year-old Clarence Morse, who doesn't mind admitting that sixty-five years ago he tried his hand at smuggling alcohol. “1 did it a few times, but 1 didn't like it-there were just too many risks. The money was good, especially considering how tough times were, but it wasn't worth dying for,” he said, “and some did.” Morse said he feels no shame about his brief stint as a bootlegger; he figures he was only doing what was necessary to survive desperate times, and he'd do it again under the same circumstances. Morse was born on April 19, 1908, in Jay, Vermont, to Herbert and Pearl Morse. He grew up in the neighboring community of North Troy, an Orleans County village bordering Quebec to the north and the Green Mountains to the west. Because North Troy was on one of Orleans County's busiest rum-running routes, the village became a popular stopover point for out-of-town smugglers. Notorious gangsters passed through town, and unsubstantiated stories even have Chicago gangster Al Capone staying overnight in a small North Troy hotel.

Loads of booze also came across the border in boats

Morse is a man with a quick wit and a true gift for storytelling. Coming of age in the middle of Prohibition, Morse said that he nevertheless learned to enjoy having a few drinks, and he and his friends didn't let Prohibition stop them from indulging in that pleasure. They visited some of the so-called line houses, which were unlicensed drinking establishments common along the United States-Canada border, especially during Prohibition, when drinking remained legal in Canada. Many of the houses were entirely in Canada, but others were built right on the line. Though Canadians frequented them, they attracted many American customers as well, some of whom traveled hundreds of miles from southern New England and beyond in a boozy Prohibition pilgrimage. Others, more business-minded, went to the line houses to pick up shipments of alcohol. Some visitors did a little of both.

The nearest line houses in Morse's area were right across the border in Highwater, Quebec. “The Labounty Line House was one of the most popular,” Morse said, remembering many trips there with his friends. “The house was split right in two: half was in Canada, half in the States. Some people went there to drink, and many to pick up loads of booze destined for Barre, Vermont, about seventy miles to the south.” Morse recalled that Barre served as a depot for much of' the alcohol that passed through Orleans County. The alcohol was warehoused there until distributed to other locations in Vermont and throughout New England.

Small time smugglers brought booze across the border on the backs of horses

Also in attendance at the line houses were “the moneymen,” who worked to entice locals to take the loads for them, according to Morse. “They'd say, ‘Can you take a load to Barre?' I didn't bother with them too much. These moneymen were making a fortune, and the others were taking the chances.” Morse said he doesn't know who the moneymen were, but they seemed to be closely connected with the operation in Barre. Local men, who knew the roads well and were willing to drive the contraband, were offered $125 for the journey, a night's work.

The trip down took two to three hours-as long as the driver didn't run into any problems with the police along the way. “That was more money than I could make in three months,” Morse said, who, at that time, was making seven dollars a week working on the town's road crew. Times were tough and money was hard to come by. Many people were sorely tempted, and the moneymen used a variety of techniques to win over the reluctant runners, including offering them free beer while discussing the proposition. “They'd get fellows so hot that they'd take a load,” Morse said. “A lot of the guys who did it were just trying to make a few bucks to get along. Usually they were just young fellows. They weren't bad people.” When sober, Morse related, his good sense prevailed, and he could resist their offers; but with each additional free beer, the importuning became more difficult to resist. “Well, the next thing I knew, a couple friends and I were loading up a car with booze.”

The loads typically consisted of ten cases of beer, Molson or Genesee, and one case of liquor. “At that time a case of beer was twelve quart bottles,” Morse explained. The bottles were often carried in burlap bags. No money exchanged hands until the load was delivered. “Back then a man's word was better than anything written on a piece of paper.”

Morse said that the cars headed south from Highwater into Vermont, making their way south through Westfield, Waterbury, and Montpelier, the state capitol, before arriving in Barre. This wasn't always an easy task, Morse said. “Professional drivers knew enough not to drink before a run, because they knew the importance of a clear mind for outwitting the lawmen who lurked in waiting for the alcohol-laden cars flowing south from Quebec. Many of the local boys were too naive to know this, or too chicken to run a load without a few drinks. Many of the people who were caught or crashed did so because of poor judgment brought on by drinking.”

Once in Barre, drivers took the cars to a five-bay garage that served as a transfer station. “You had to pull into one of the bays, walk out, close the door, walk into town, and come back in an hour. When you got back to the garage, the load was gone, and there was $125 on the seat,” said Morse. “You never met anybody at all. That was quite the business. “And it was a dangerous business,” Morse added. “It was no game.” In those days, lawmen could take more extreme measures to stop vehicles than they are allowed today, including shooting out the tires and radiators of fleeing cars. “The greatest danger arose because of the fact that not all of the officers were good shots,” Morse remembers one rumrunner who was killed during a chase, by accident. The driver attracted the attention of men in the town of Jay.” They followed him through Jay and shot as he was going down the hill into Westfield. They killed him. They really didn't mean to kill him; they just meant to stop him,” Morse said. That man was Winston Titus and the date was July 1927. The death was on the front page of many of the state's northern newspapers for weeks following the incident. The first papers to hit the newsstands reported that Titus died instantly hen his alcohol-laden car crashed into a tree while he was being pursued by Immigration road patrol officers Nelson Hines and Joseph Faucher. The articles made no mention of any gunshots being Rumors, however, quickly spread around the county asserting hat the “accident” was caused by shots fired by the two officers. The St. Johnsbury based Caledonian-Record ran the following article in the July 25, 1927 issue. “The death of Winston Titus, a youth under 20 years of age, which occurred in Westfield about 2:20 Wednesday afternoon, is a mystery which federal and state officers are investigating.

The boy, who lived at North Troy, was in a high-powered but old touring car, containing 18 cases of ale brewed in Montreal. Immigration patrol officers gave out a story that he was instantly killed when his car struck a tree and turned over, pinning him under it.

However, it is reported that two bullet holes were found by undertakers in his body, and Mrs. Walter D. Bell, close to whose farmhouse, a mile north of here, the death occurred, heard two sounds which she described as shots fired from a heavy revolver.

The rear curtains on the sides of the car have been stripped off. It was reported this was done by State's Attorney Brownlee, who was soon on the scene, and there is a big hole made apparently by a bullet, about the place where the rear cushion in the car would be. This cushion, it is said, was also carried off by officers.

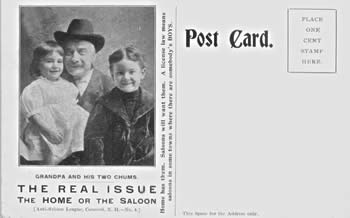

There were many staunch supporters of this country’s Prohibition laws

The Titus boy was of an excellent family of North Troy, and had a good reputation.

Wednesday morning he helped his father in the hay field, and at noon went to the village to have his hair cut and get a shave, and planned to return to work. His father had no knowledge that he ever ran liquor past the border officials. The car which was in this smash-up was bought for a song three days previously at a sale of seized rum-running cars, as told by George Rolfe, who was reported to be in the liquor business just beyond the line. It was declared that the Titus boy was not an old or frequent rum-running offender. He came across the border, it is alleged, by a rough country road, which a horse and buggy would find difficult, going through North Jay and Jay, and it is reported here that he was being fired at by officers as he went through both places.

Two Immigration officers who had parked a small but specially geared car at North Jay, looking for liquor or immigrant smugglers, ordered him to stop near the line, but he would not. They kept close after him.

Mrs. Bell says that she heard the two cars coming very fast, so fast that she suspected a rum runner chase, and just after they passed she heard two loud reports, which she feels sure were caused by a large revolver.

The car about that instant struck two trees on a five-foot high bank about 100 yards below her home, and turned over in the air, falling on its top in the road and crushing Titus frightfully. The right-hand wheels were ripped from the hubs, one of them leaping a wire fence and running 155 feet before stopping.

Officer C. C. Stannard of Lowell, who was passed by the car and its pursuers just in front of Mrs. Bell's home, telephoned at once to State's Attorney Brownlee and to undertaker Jackman of Newport.

Several officers were on the scene within an hour after the boy died. The Immigration officers who chased him are reported to have been patrolmen Faucher of Newport and Hines of Montreal, the latter a new man in this region, who the day before chased and captured a man more than twice his size.” An autopsy on Titus' body confirmed what many people already believed: Titus had been shot, a fact that sent renewed shock waves throughout the state. The Caledonian-Record reported the following in the July 29, 1927 issue:

The report of the autopsy on the body of Winston Titus, 20 years old of North Troy, who met death while being pursued by two Immigration officers, shows that two bullets went through the boy's body, Attorney General J. Ward Carver announced this morning. ‘The autopsy showed,' Mr. Carver said, ‘that one of the bullets entered the back of the boy's head near the brim of his hat and came out the forehead, while the other one entered under the left shoulder blade. Either of the wounds, the doctors claim, would have caused the death.

The two officers were arrested and charged with manslaughter.

They were each released on $3,000 bail. A grand jury hearing into whether to indict the two officers for Titus's death was convened on August 2, 1927. The findings of the jury were swift and in the officers' favor. After listening to about twenty witnesses, the jurors failed to find evidence to support charges against the two officers.

Mr. Titus's death caused some people to question Prohibition, while others remained staunch supporters. The St. Albans Messenger jumped into the fray by writing an editorial that caused at least one other paper in the state to respond:

“Uniformed officers of the federal government again sacrifice a human life in their over-zealous desire to enforce the law. A citizen of North Troy returning from Canada in his car drives rapidly over the road and is seen by Immigration officers who immediately suspect him of smuggling aliens into this country, so they shout to him to stop and upon his refusal to do so, put after him and in the course of the chase fire at him, his car swerves and hits a tree, and he is removed from the wreckage a dead man.

It may be that the Immigration officers really thought that an alien was illegally entering this country, but an alien alive in this expansive country cannot in any way be as serious as the taking of a human life.

This law enforcement to the extent of taking of life is something that the citizens of the country should no longer tolerate.

The claim that the shooting was done by a young and inexperienced man does in no way relieve the blame on the department. Such things should be impossible. If the new men were given proper instructions at the time that they are sworn in, many of these shooting affairs would never take place.

True, the government does not pay sufficient salary to attract extra high-class men to the service, but if the service is so vital that human life must be sacrificed on the altar of law enforcement, then the government should either increase the pay or take away firearms from this admittedly inferior class of public servants.

It is long past time that this opera bouffe as played along our border be stopped, and if those in charge of border affairs are not capable of enforcing the law with reason and without the loss of life, then they should be removed as incompetent and should be replaced by men who are.

In the meantime, none of us are safe and are liable to meet the fate of Winston Titus at the hands of some hot-headed, cheap boy who has no more brains than to think that as soon as he is sworn in and gets into a fancy uniform with a gun in his band, he is now greater than human life itself.

The Messenger has been and always will be in favor of law enforcement, but does believe that the enforcement should be made with reason and not by cheap public servants with guns in their hands.

We hope this North Troy case may be tried promptly and thoroughly so that we may know whether or not we have the right to ride along the border without running the risk of being shot by some over-zealous armed officer who thinks that a uniform and badge is a license to take life if his dictates are not followed at once.

Not all editors around the state agreed with those at the Messenger. An editorial by the Express and Standard in Newport took the St. Albans paper to task for its views of the shooting:

It is true that the taking of human life is an awful thing. Even when the state takes a life as penalty for murder we shudder. But the question recurs: What method is to be pursued to enforce law?

We who live along the Canadian-Vermont border have been called upon from time to time to witness such tragedy as that which took place on a back road in the town of Westfield last week. An officer of the law, in the course of his duty, is charged with killing a lawbreaker. Should such a thing ever happen? The St. Albans contemporary says, ‘This law enforcement to the extent of the taking of life is something that the citizens of the country should no longer tolerate.' Does the Messenger really mean this?

A burglar enters a bank, holds up the employees, empties the tills of $25,000, and attempts his getaway. Should an officer in pursuit of the thief use a revolver in an effort to capture him? We submit the question to the Messenger.

A neighbor attempts to satisfy an imaginary wrong by setting fire to your buildings. Should an officer who sees the committer of arson attempting to escape use a revolver in an effort to capture the criminal? We submit that question to the Messenger.

A fiend in human form attempts rape upon your daughter. Is an officer justified in the use of a gun in stopping the escape of such a lawbreaker? We submit this question to the Messenger.

We understand perfectly well that the degree of crime and the circumstances surrounding it often make the result of enforcement, or attempted enforcement, appear stupid or brilliant, as the case may be. But the doctrine that the offender should always be guaranteed safe escape if he has a faster car than the officer, is, in the opinion of the Express and Standard, not only dangerous but also stupid.

We have heard this preachment of criminal freedom from danger repeated over and over in different forms ever since our border problems, because of new immigration laws and Prohibition, became more numerous and offensive. But we never heard such blanket disapproval of the use of this most effective instrument against aggressive criminality, the officer's gun, before.

Does the Messenger really think that the people want no enforcement methods against law breaking which endangers the life of the criminal? Must lawbreakers always be given the ~long end' of the enforcement problem?

Perhaps the Messenger has some constructive plan of enforcement which would bring results and at the same time put the lawbreaker at ease while committing offences against the law in so far as endangering his life is concerned. If so, we believe both state and national governments would be only too glad to adopt them, for least of all these governments want to take innocent lives. We have heard this railing against accidents which now and then snuff out the life of one who fails to obey the usual courteous command of an officer, but we have never yet heard a constructive suggestion for its remedy and still leave any teeth in enforcement.

The death of young Titus has not yet been proven to be from the use of an officer's gun. Whether it is or is not such result, his death is unfortunate and untimely, and the Express and Standard regrets it exceedingly. But our border problems are difficult ones and need the constructive sympathy and help of people and the press. These problems come under the general title of law enforcement. Too many people believe in law enforcement, but always but. The way, or the method, or the means, or the sentiment of the people, or something with the enforcement as attempted is wrong.” Morse said he knew Titus and can still well recall his death all the commotion that followed. He speculated that the officers probably were trying to shoot holes in the tires or gas tank, located to the rear of the car. Morse believes that the officers accidentally shot high, missing the tank and killing Titus. Morse said the car hit one big tree so hard that evidence the crash remained at the site for years afterward, including the starter crank, which was originally attached to the front of Titus’s car, but was now embedded in the tree.

Morse said he was never shot at during a chase, but he does know what it feels like to have a lawman tight in hot pursuit. During one run to Barre with two friends, somewhere below Waterbury our Model T Ford attracted the attention of a police officer.” The chase was on.

The two cars stepped on it, while Morse and his partners tried to figure out how to outsmart their pursuer. The driver headed down a narrow dirt road, got out of sight of the officer, then unloaded the booze and Morse onto the side of the road, where Morse hid himself and the shipment in the woods. The plan was for the other two men to shake the officer, then return and pick up Morse and the cargo. “After zigzagging along on the back roads, the driver and his passenger thought they had ditched the officer, so they returned to pick me up.” To their surprise and dismay, soon after retrieving Morse and the freight, the officer was tight behind again. Realizing that the chances of losing the policeman were slim, and that they had a better chance of escaping on the, the driver stopped the car. Morse and the other passenger ran while the driver, who was too scared to move from his seat, was arrested and jailed.

“They caught him right in front of the statehouse in Montpelier, only a few miles from Barre,” Morse said. “We didn't have a car so we went all the way home on foot. It was quite a walk.” Another local man later drove to Montpelier and bailed the driver out of jail.

Back to the good old days?

The trips to Barre were always risky, Morse noted, and they seemed especially so after he married Marie Arel and started a family that would eventually number nine children. By the time the country was thrown into the Great Depression in 1929, Orleans County was in straits more dire than it had ever experienced before. Nonetheless, Morse had already decided that bootlegging wasn't for him, so he focused his attention on making money legally. “People did anything to find money for food,” Morse said. “At one time during the Depression, I was so poor that I didn't have enough money to buy bullets for my gun, so I used snares to catch rabbits to have something to eat. I was always a guy who worked hard and always found work.”

Prohibition was a bad idea, in Morse's estimation. It wasn't hard for most people to get alcohol if they wanted it, and smuggling alcohol was too tempting for those who were desperate to feed their families. “People had to make money any way they could. There was no welfare then, and people who accepted help from the help were called ‘town paupers,' a title one was unwilling to accept for any amount of money.

“I could have managed to survive without smuggling, but life could have been a whole lot tougher, and besides that,” he chuckled, “sometimes 1 enjoyed the excitement smuggling brought with it.”

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe to our email list for the latest news!